Midway through President Joe Biden’s four-day trip to Ireland in April 2023, Representative Mike Quigley of Illinois realized whom the president reminded him of and why.

The proudly Irish president was in great spirits, energized by the crowds. In Ballina, he delivered a speech to one of the biggest audiences of his political career. Standing in front of Saint Muredach’s Cathedral, the president recalled that 27,000 of the bricks used in its construction were provided in 1828 by his great-great-great-grandfather, Edward Blewitt, for £21 and 12 shillings.

“I was able to hold one of them in my hand today,” the president said. “They’re damn heavy.” The crowd laughed.

It was a homecoming in many ways. The president had brought with him his sister, Valerie, and son Hunter. They went to see a memorial plaque to Beau Biden at the Mayo Roscommon Hospice. One of the priests at the Knock Shrine turned out to have given Beau last rites in 2015, a revelation that brought the president to tears. In a speech to the joint houses of the Irish Parliament, the president said it was Beau who “should be the one standing here giving this speech to you.”

In Dublin on Thursday, April 13, Biden was welcomed to Áras an Uachtaráin, the official residence of the president of Ireland. The busy schedule included a tree-planting ceremony, a ringing of the Peace Bell, and an honor guard presenting arms.

At one point, the room Biden was in emptied out and fewer than a dozen people were left—including Quigley and his friend Brian Higgins, then a congressman representing New York. Hunter took advantage of the lull to impress upon his father the need to rest.

“You promised you wouldn’t do this,” Hunter said. “You promised you’d take a nap. You know you can’t handle all this.”

The president waved off his son and walked over to the bar in the back of the room, where a lone woman was working. She served him a soft drink. He seemed utterly sapped and not quite there.

And that was when Quigley realized why the scene felt so familiar: The president’s behavior reminded him of his father’s in his final years; he had died of Parkinson’s in 2019, at the age of 92.

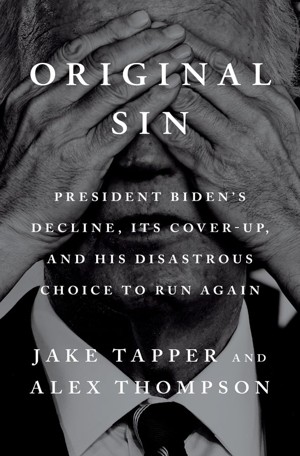

Some Democrats, perhaps chief among them the former president himself, still deny that his very real deterioration happened. On The View earlier this month, the co-host Alyssa Farah Griffin, referring primarily to our forthcoming book, Original Sin: President Biden’s Decline, Its Cover-Up, and His Disastrous Choice to Run Again, asked the former president about the “Democratic sources” who “claim in your final year, there was a dramatic decline in your cognitive abilities. What is your response to these allegations, and are these sources wrong?”

“They are wrong. There’s nothing to sustain that,” Biden said.

For our book, we spoke with more than 200 people, overwhelmingly Democrats, many of whom worked passionately to pass Biden’s agenda. They included Cabinet secretaries, administration officials, and members of Congress.

Almost all of them would talk with us only after the election, and they told their stories in sadness and good faith.

People such as Mike Quigley.

Quigley’s father, Bill, was abandoned as an infant at an Indiana orphanage, then adopted by a World War I veteran and his wife. The application form asked what gender child they preferred to adopt. “Any child we can love,” they wrote. Bill took his dad’s name and, when he was old enough, worked with him on farms as a handyman. Drafted into the Army during the Korean War, Bill became a member of the Signal Corps, learning skills that would get him a postwar job at AT&T for 35 years. Bill never finished college, but he worked hard and built a loving middle-class life for his family. He was his son Mike’s hero.

Bill’s last years were tough. Parkinson’s is a brutal disease. Because he lived in a small town, his problems were initially misdiagnosed, but the deterioration was unmistakable, and it was difficult on the entire family. When everyone showed up at family functions, Bill would get an adrenaline boost. When the high wore off, though, it was akin to witnessing all the air empty from a balloon. For Mike, watching his father deflated and drained was heartbreaking.

[From the January/February 2020 issue: What Joe Biden can’t bring himself to say]

And as he watched Biden during that April 2023 trip, Mike Quigley thought it all looked very familiar. The president hadn’t yet officially announced that he was running for reelection, though it was expected. How can he do this? Quigley asked himself.

The president gained strength from the adoring Irish crowds. And away from them, he seemed as if all the life had left him.

Biden, Quigley thought to himself, needed to go to bed for the rest of the day and night. He wasn’t merely physically frail; he had lost almost all of his energy. His speech behind the scenes was breathless, soft, weak. There was so much about the president on this trip that reminded Quigley of his dad.

Quigley told Brian Higgins how much the president’s symptoms seemed Parkinsonian. But Higgins had his own frame of reference. He had lost his father to Alzheimer’s and thought he was noticing something familiar in the president’s shuffling.

“A diagnosis is nothing more than pattern recognition,” Higgins would later tell us. “When people see that stuff, it conjures up a view that there’s something going on neurologically.”

[Helen Lewis: Biden’s age is now unavoidable]

The president’s deterioration became pronounced in 2023, the year of the Ireland trip.

Quietly, Democratic officials were beginning to wonder whether the president was in cognitive decline—“which was evident to most people that watched him,” Higgins said.

After all, the fate of the nation depended on Biden’s ability to mount a strong reelection campaign.

On the floor of the House and in caucus meetings throughout 2023 and early 2024, House Democrats who had witnessed such moments—although only a few, because access to Biden was so limited—talked about what they’d seen and what they could do.

Quigley wondered why the White House physician didn’t pursue a diagnosis to see what was wrong with the president—but, he figured, perhaps Biden’s staff simply didn’t want to know.

He also felt as if he had no good options. He could talk about what he’d seen, he could lament it, but he and other Democrats asked one another: What the hell could they actually achieve? At the end of the day, all they would likely accomplish would be angering the president.

In 2023, with Donald Trump facing fierce legal headwinds and strong GOP challengers—Nikki Haley, Ron DeSantis—some Democrats’ concerns about Biden’s decline were tempered by their erroneous belief that Trump couldn’t win, which lowered the stakes.

The consensus among these Democrats was that going public with their concerns would serve only to get them in a lot of trouble. Biden was going to be the nominee—no one serious was challenging him in the primaries—so why would they want to draw attention to his decline?

Their concerns about Biden were not the stuff of right-wing conspiracists. They were worried because people they loved had fallen victim to some of the cruelties that time delivers. And frankly, they were late to the realization. The American people had been expressing serious concerns about Biden’s abilities, because of his age, for years.

Concerns over the age of presidential hopefuls weren’t even specific to Biden.

In 1991, the Democratic vice-presidential nominee from the previous election, Senator Lloyd Bentsen of Texas, hired a young pollster named Geoff Garin to secretly explore the prospect of Bentsen running for president the next year.

Garin ran the numbers and came back to the Texan with bad news: Voters thought that the senator, at age 70, was simply too old.

More than 30 years later, Garin did polling for Biden and saw much the same result. In a way, the argument was irrefutable. The American people might have been confused about tariffs, unsure of how to tackle the deficit, and uncertain how to handle the challenges of the migrant crisis, but they understood what aging does. They had seen their grandparents and parents go through it. And they did not want a president navigating those challenges.

In October 2022, one of us, Jake, got a chance to interview Biden, his last such opportunity. Biden was not the man Jake had interviewed in September 2020—he was slower and stiffer, his voice thinner—but his responses were razor-sharp compared with his performance at the June 27, 2024, debate that Jake co-moderated with Dana Bash on CNN.

In that October interview, after noting that Biden was about to turn 80, Jake said that whenever anyone raised concerns about his age, Biden would always say, “Watch me.” But voters had been watching him—and one poll showed that almost two-thirds of Democratic voters wanted a new nominee, mainly because of Biden’s age.

[Read: How Biden destroyed his legacy]

“Well, they’re concerned about whether or not I’d get anything done,” Biden said. “Look what I’ve gotten done. Name me a president, in recent history, who’s gotten as much done as I have in the first two years. Not a joke. You may not like what I got done. But the vast majority of the American people do like what I got done.”

That wasn’t particularly true—more than two-thirds of the country thought the nation was on the wrong track, and Biden’s approval rating was underwater—and it was also not the question Jake had asked. The president and his inner circle had assessed his age as a political liability, but they hadn’t stopped to consider the question of his actual ability. They sought to hide the fact that vigor was a commodity in scarce supply.

The president and his team were delighted by his lively performance at the 2024 State of the Union. Afterward, when Biden came down onto the floor of the House of Representatives, he was swarmed by adoring Democrats.

Quigley hadn’t been so close to Biden since they were in Dublin almost a year before. He put his hand on the president’s back. He could feel his ribs, and his spine. It seemed weird to consider, but it made him think of what it would be like to touch the aged, feeble Mr. Burns from The Simpsons. The president’s voice was soft and breathy. His eyes darted from side to side. Quigley was again disconcertingly reminded of his late father.

The president’s disastrous debate performance a few months later was not a tremendous surprise to Quigley.

“We have to be honest with ourselves that it wasn’t just a horrible night,” Quigley told CNN’s Kasie Hunt on July 2. A few days later, he became one of the first Democratic officials to call for the president to step down from the ticket. He was reminded of when he’d had to take the car keys from his mother, who was losing her vision.

The response was predictable. “What the fuck are you doing?” one colleague asked him. “It’s too late!” said another.

Then-Representative Dean Phillips of Minnesota had tried to sound the alarm about all this in 2022, vainly attempting to recruit midwestern governors to challenge the incumbent president in the primaries before ultimately launching his own campaign. Drawing attention to the president’s declining acuity was pretty much his only issue. The party apparatus circled around the president like the Praetorian Guard, shielding him from debates and trying to keep Phillips off ballots. Given his lack of traction in polls, Phillips soon disappeared. When Special Counsel Robert Hur, who had been investigating Biden for improperly possessing and sharing classified materials, tried to discuss the president’s memory and presentation when explaining his decision not to prosecute, the Democratic Party and White House painted him as a right-wing hack. Journalists who raised the issue were viciously attacked by lawmakers and besmirched on social media.

Quigley experienced some of the same treatment.

“If you bring this up publicly, you’re just going to hurt him,” one representative told him.

“What difference does it make?” said another. “He’s the candidate no matter what, so everyone should shut up.”

“You’re a traitor!” a fellow member of the Illinois delegation told Quigley after he went public. “It’s ageism. You’re going to make us lose!”

This past March, town halls for both Democratic and Republican elected officials were so packed with angry constituents that some members of Congress opted instead for virtual meetings that were easier to control, or skipped them entirely. Quigley relished chatting with Chicago communities, despite getting earfuls of complaints. He’d been doing it for 47 years, first as an aide to an alderman and then serving on the Cook County Board of Commissioners before his election to the House.

But this spring, the vitriol aimed at Senate Democratic Leader Chuck Schumer and Illinois’s own Senator Dick Durbin has been over-the-top. Quigley has never seen anything like it.

“They go back to the original sin,” Quigley said, explaining their anger at Biden’s decision to run for a second term. “They perceive that he was selfish. He couldn’t see that he couldn’t win.”

People appreciated that Quigley was one of the first Democratic officials to publicly call for Biden to step aside. “But it was too late,” one activist told him. She was angry at the party’s leadership, but most of all, at Biden. “They couldn’t let their egos get out of the way,” she said. “He saved our democracy and then he doomed it again.”

Quigley sensed that Democrats were going to be mad for a long time about the refusal of Biden and those around him to acknowledge what was happening to him.

What’s more, Quigley knew they were right.

This article has been adapted from Jake Tapper and Alex Thompson’s forthcoming book, Original Sin: President Biden’s Decline, Its Cover-Up, and His Disastrous Choice to Run Again.