Editor’s Note: This article is part of “The Unfinished Revolution,” a project exploring 250 years of the American experiment.

Patrick Henry is generally treated as a second-string Founding Father. He didn’t write—or even sign—the Declaration of Independence. He didn’t write the Constitution. Instead, fearing that it allocated too much power to a centralized government, he did all he could to defeat it. He was not a Revolutionary military hero. He did not explain lightning, invent bifocals, take Paris by diplomatic storm, or write an autobiography that has become a classic in American literature. Henry did attend the First and Second Continental Congresses, but made little mark. After 1775, he remained in his home state of Virginia, where he would serve five terms as governor. He did not again take up national service.

What Patrick Henry did above all was talk—and get talked about. He astonished his listeners as the most compelling public speaker they had ever encountered. He was, John Adams proclaimed, the Demosthenes of his age. Thomas Jefferson hailed him as “the greatest orator that ever lived.” In the opinion of Edmund Randolph, the country’s first attorney general, Henry’s eloquence “unlocked the secret springs of the human heart, robbed danger of all its terror, and broke the keystone in the arch of royal power.” Many of his contemporaries agreed that he made the Revolution possible with words that rendered it both desirable and inevitable.

He certainly had no rhetorical rival among the other Founders. George Washington was frightened of public speaking, and trembled visibly during his first inaugural address. When a speech was required of him, Jefferson customarily spoke so softly that he could scarcely be heard. Benjamin Franklin offered copious advice on rhetoric to others, but himself preferred print to oratory. His most famous “speech”—urging unity at the Constitutional Convention in 1787—was a written text that he gave to another delegate to read aloud. James Madison, in spite of his brilliant legal mind, was a nervous speaker, with a shrill and off-putting voice.

Henry reminds us of how our inability to hear the past before the advent of audio recording has left us with an incomplete and even distorted understanding of history. He lived in an era when the spoken word had not yet been overtaken by the power and reach of print. This was a time—and Henry was a figure—we can only poorly understand if we do not recognize the centrality of oratory.

An assiduous scholar has located nearly 100 responses by individuals who heard Henry’s speeches, so we at least have secondhand access to the impact of his words. We can’t retrieve his voice, but we can find accounts of how it made audiences feel. As one contemporary explained, there was “an irresistible force to his words which no description could make intelligible to one who had never seen him, nor heard him speak.” On a trip through Virginia as a young man, the future president Andrew Jackson sought out the orator he had heard so much about. “No description I had ever heard,” he reflected, “no conception I had ever formed, had given me any just idea of the man’s powers of eloquence.” Patrick Henry had become a tourist attraction.

We can’t even read Henry’s most important speeches. The potency of his rhetoric derived in no small part from its extemporaneity. He left no texts or notes of his Revolutionary-era addresses, and observers described being so swept up in the moment that they were unable to document his performances. “No reporter whatever could take down what he actually said,” the Virginia judge Spencer Roane remembered. “Much of the effect of his eloquence arose from his voice, gesture, etc., which in print is entirely lost.” Today, Henry’s legacy is left chiefly to schoolchildren tasked with memorizing and reciting a reconstruction of his “Liberty or Death” speech of 1775, pieced together by his biographer William Wirt from witnesses’ testimony two decades after his death.

Henry clearly possessed a particular genius. But his gift took on great significance because of the time and place in which he was able to use it. The rhetorical style that Henry embraced to advocate for the Revolution was a revolution in its own right. Casting himself as a “plain man,” he ignored prevailing conventions of classical oratory that foregrounded carefully reasoned addresses influenced by the teachings of Cicero and Quintilian. Instead Henry regarded the human heart, not the mind, as the appropriate target for his words. His intended audience was not just the small world of learned men, but the far larger one of ordinary citizens—many with meager, if any, education—whom he sought to move as much as persuade. “Your passions are no longer your own when he addresses them,” George Mason, the Virginia planter and politician, observed. Henry’s was a popular and democratic, rather than elite, rhetoric. At the same time, his critics saw it as potentially—and dangerously—demagogic. Edmund Randolph explained that Henry was “naturally hailed as the democratic chief.”

Embracing Henry was, in the minds of many Virginia aristocrats, a bit like supping with the devil. Jefferson admired him extravagantly, but belittled him as well, deploring his coarse appearance and vocabulary, his seeming lack of learning. But that vulgarity was exactly what Americans needed as they sought to mobilize against British rule. Henry was, in Jefferson’s view, vulgar in the sense of “offensive to elevated taste.” But he was also vulgar in the sense of “pertaining to the common man.” Virginia’s Tidewater aristocrats accepted the first in order to leverage the latter. They needed a people aroused in support of independence, even as they understood what empowerment of the people might ultimately imply for their own status and control. In 1824, Jefferson confessed that it was “not now easy to say what we should have done without him.” Henry’s speeches transformed both political discourse and American politics.

Whereas the scions of Virginia’s elite resided in brick mansions in the Tidewater, Henry came from the more rugged Piedmont region of the interior. His father was a well-educated landowner and enslaver, but lacked the refinement and status of the Byrds or Carters or Randolphs. Henry had a haphazard education, and at about the age of 10 left school to be tutored by his father. He at first scrambled to make a living, working as a store clerk, toiling in the fields as a farmer, and running a tavern before finding his way to the law—not through formal education but after a series of individual examinations with prominent jurists.

His Piedmont home provided a different sort of education. In the 1740s, a series of religious revivals swept through the Virginia backcountry, sparked by the preaching of the extraordinary itinerant English evangelist George Whitefield, then carried forward by a Presbyterian minister named Samuel Davies, who, as one observer noted, turned Henry’s Hanover County into “the suburbs of Heaven.” Henry heard Whitefield preach in 1745, when he was only 9 years old. After his mother became a devoted adherent of evangelical Presbyterianism, sermons and religious rhetoric became a central part of young Henry’s life. She took him regularly to hear Davies and made him repeat the essence of each sermon on the way home. Henry was transfixed by the power of Davies’s words and always acknowledged the minister’s influence.

Davies represented a phenomenon that extended well beyond Virginia. Whitefield had traveled close to 5,000 miles up and down the Atlantic Seaboard, speaking to substantial crowds on some 350 occasions. His tour had sparked revivals throughout the colonies, with preachers such as Jonathan Edwards in Massachusetts and Gilbert Tennent in New Jersey, as well as Davies in Virginia, building on his message after his return to England. As the first colony-wide, American experience, this Great Awakening was a harbinger of things to come. But it represented more than an initial example of intercolonial connection. The message of the new evangelical preaching was one of the heart and the emotions, not just of learning and reason. It offered the hope of salvation to all its listeners, regardless of education or social standing. It was an implicit and sometimes explicit challenge to privilege and status.

In Virginia, the wave of conversions in the 1740s was followed by a second surge of evangelical fervor in the 1760s, once again in areas near Henry’s home, but this time focused among Baptists and even more democratic in its implications. Authorities regarded these eruptions, chiefly coming from lower-class and uneducated white people, as a threat to the social order that required suppression and even arrests. Henry was an active defender of the right of Baptists to preach and assemble and was even said to have ridden an extra 50 miles on one occasion to offer his legal services to a group of Baptists jailed in Spotsylvania County for disturbing the peace.

From his experiences in Hanover County as the son of an evangelical mother, Henry brought rhetorical influences and democratic impulses to his public life. His voice became one dedicated to conversion—though in the realm of man, not of God. Henry rapidly established himself as a country lawyer. His courtroom successes created widespread demand for his services as well as a considerable stream of income. His extensive speculation in lands in western Virginia and Ohio contributed to his growing wealth, and he acquired more than 60 enslaved workers. Henry’s oratory would establish him as a voice of the people, but economic and social circumstances placed him among Virginia’s privileged gentry.

The speech that vaulted Henry into political prominence came during a 1763 court case that was known as Parson’s Cause. Voicing the resentment of ordinary Virginians against the clergy of the established Anglican Church, Henry advanced arguments well beyond the tenets of prevailing law. Instead, he successfully appealed to the jury with abstract—and inspiring—principles of local self-determination in the face of what he characterized as monarchical tyranny. Henry’s rhetoric foreshadowed positions he would soon take against presumptions of British power. Just two years later, as a new member of the House of Burgesses, he proposed what came to be known as the Virginia Resolves, instigating the colonies’ unified opposition to the Stamp Act. Henry soon became one of the earliest advocates for American independence. His success as a lawyer and as a political speaker derived in no small part from his tactic of elevating specific issues into the transcendent realms of justice and virtue. He inspired his audience with a changed understanding of what was at stake, casting his arguments as matters of life and death.

Henry delivered his legendary “Liberty or Death” speech on March 23, 1775, at the meeting of the Second Virginia Convention in Richmond’s Henrico Parish Church. The colonies were already well on their way to war with England, which would begin just a month later at Lexington and Concord. The First Continental Congress had the previous fall created a Continental Association committed to resisting British incursions on American rights, and Virginians were assembling to prepare for the conflict that was coming to seem inevitable. The decision to meet in Richmond, a modest town 50 miles beyond the reach of the royal governor in the capital of Williamsburg, was itself an indication that the representatives recognized the boldness of their actions.

Yet many members of the Virginia gentry remained nervous about what lay ahead and uncertain whether preparation was simply prudent or would in itself escalate differences and make reconciliation with Britain impossible. These men of status, reputation, and means were not yet ready to risk their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor. It would be Patrick Henry’s job to get them there.

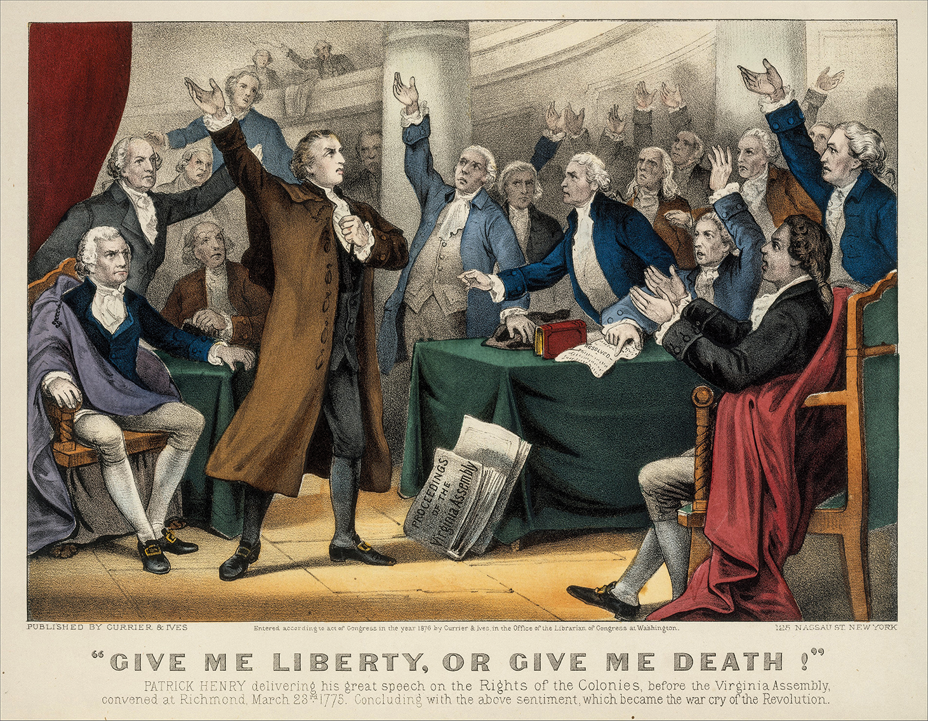

Some 120 Virginians, including such worthies as Jefferson and Washington, gathered on a hill high above the James River, crowding into the pewboxes of the wood-framed church, the largest structure available in a town that had only recently grown to 600 souls. After lengthy discussion ultimately approving the work of the Continental Congress, Henry rose on the fourth day of the convention to ask the clerk to read a set of resolutions proposing that “this Colony be immediately put into a posture of defence.” The time had come for “embodying, arming, and disciplining” a Virginia militia, he maintained. When cautious delegates objected to such a public declaration of military mobilization as unduly provocative, Henry responded with his famous speech.

The text that schoolchildren have declaimed and aspiring orators have studied since the early 19th century was derived from recollections that the distinguished jurist St. George Tucker provided to Wirt, Henry’s biographer, sometime between 1805 and 1815. Tucker was present at the convention to hear Henry speak, and judged that “nothing has ever excelled it, and nothing has ever equaled it in its power and effect.” The version he provided for Wirt and for posterity rests upon the accuracy of his memory of a day more than three decades earlier. Historians have sparred for more than two centuries now over the reliability of this rendering. William Safire, the late journalist, presidential speechwriter, and authority on language and rhetoric, offered the measured assessment of an informed critic: “My own judgment is that Patrick Henry made a rousing speech that day that did conclude with the line about liberty or death; that a generation later, to respond to the wishes of his friend writing a biography of the patriot, Judge Tucker recalled what he could and made up the rest. If that is so, Judge Tucker belongs among the ranks of history’s best ghostwriters.” A unique ghostwriter whose work followed rather than preceded the text.

Henry customarily appeared in public in simple, sometimes even stained, rustic clothing—caring, a contemporary remarked, “very little about his personal appearance” and on occasion seeming as if he had come fresh from the hunt. For a gathering of the colony’s most prominent citizens, Henry likely chose more respectable clothing: a plain dark suit appropriate to his presentation of himself as an ordinary man. At odds with expectation and elite fashion, Henry usually wore a shabby, unpowdered wig. Observers described how Henry impressed audiences with his look of severity, his piercing blue-gray eyes in constant motion beneath thick, dark eyebrows. He held his long, thin frame in a pronounced stoop, and the tendons of his neck conveyed his intensity, standing out “like whipcords,” one witness recalled, as he began to speak.

Critics frequently commented on the “homespun” character of Henry’s language, and Jefferson dismissed Henry’s voice and pronunciation as common and unrefined. John Page, who served on Virginia’s Privy Council while Henry was governor and was later governor himself, confirmed that Henry habitually employed such coarse usages as yearth for “earth,” naiteral for “natural,” and larnin for “learning.” He used common words to appeal to common men.

Henry was known for beginning his speeches with understatement. It was his pattern to lull his listeners into moderating their expectations by holding back on his passion and rhetorical display. Henry opened his remarks to the 1775 convention calmly, with deference to “the very worthy gentlemen” who had just spoken in support of caution and with an apology for any disrespect his expression of differences with them might seem to imply. Henry’s words were intended to appear not only as a winning act of goodwill but also as a means of establishing his humbleness before the elite Virginians from whom he wished to distinguish himself.

Yet Henry’s humility was in no sense meekness. He intended to offer his sentiments “freely and without reserve,” and overcome any “fear of giving offense.” Silence and decorum, he insisted, would not be gestures of respect but acts of treason. Henry had quickly moved from polite deference to defining “the magnitude of the subject” at hand—“nothing less than a question of freedom or slavery.” He had transported his audience and his argument into the domain of the existential. For the members of the Virginia gentry who sat before him, there could be no more palpable contrast than the one they experienced and enforced every day: the rights they prized and enjoyed enabled by the bondage of the 40 percent of the Virginia population they enslaved. The very force of the paradox made freedom seem all the more precious. They lived as perpetual witnesses to the meaning of liberty denied.

From this opening, Henry pivoted to the framework of evangelical religion as he cautioned his audience about the dangers inherent in “illusions of hope.” They must be shaken out of their complacency to seize their own “temporal salvation.” Like Jonathan Edwards, who used the image of a spider dangling over a flame to beseech his congregation to “consider the fearful danger you are in,” Henry invoked both Old Testament and New, the Book of Jeremiah and the Gospel of Mark. Were his listeners like those who, “having eyes, see not, and having ears, hear not?” he demanded. He insisted that Virginians must act, “whatever anguish of spirit it may cost.” Don’t believe any conciliatory gestures, he warned, for Britain, like Judas, will deceive you: “Suffer not yourselves to be betrayed with a kiss.”

Henry issued a cascade of rhetorical questions—partly to clarify Britain’s nefarious intentions, but also, more important, to compel his listeners to interrogate their hopes and acknowledge them as false. We don’t know whether any of his questions evoked a verbal response from the delegates. Did they shout “No!” when Henry asked, “Are fleets and armies necessary to a work of love and reconciliation?” or “Shall we resort to entreaty and humble supplication?” Perhaps. The convention seemed to reflect something of the call-and-response characteristic of evangelical and enthusiastic religion. But Henry’s questions certainly demanded soul-searching from the individuals subjected to his challenge. With the rising cadence of his injunctions—“Ask yourselves …”—he not only confronted but connected with each of his listeners. In the role of exhorter—a term often used in this era for evangelical preachers—he addressed his audience less as a convention than a congregation. Having destroyed the grounds for illusion—“Let us not, I beseech you, sir, deceive ourselves longer”—he proceeded to provide answers to his questions in a call to action: “We must fight.”

[From the February 1888 issue: Patrick Henry]

In a series of declarative phrases that recounted the fruitlessness of the colonies’ efforts to “avert the storm,” Henry made repeated use of anaphora and parallel constructions to unite his audience in the pounding rhythm of his words. “We have … we have … we have.” “If we … if we … if we.” As a young man, Henry had become known as an accomplished fiddler and often played at local dances, luring people onto the floor with his musical virtuosity. Now he invited the delegates to the Second Virginia Convention to join him as he performed his oratorical dance.

He returned to a barrage of questions that challenged his listeners to imagine the future—and the choice that was theirs to make. Would they wait, irresolute, “until our enemies have bound us hand and foot?” Or would they recognize that with God’s blessing “in the holy cause of liberty,” they would be invincible? “War is inevitable”; the alternative to action was “chains and slavery.” Henry could have chosen no more threatening or motivating an image.

By establishing the premise that war was unavoidable and by raising the dread specter of enslavement as the inescapable outcome of inaction, Henry recast Virginians’ choice as no choice at all. Yet a few voices from the floor still called out “Peace! Peace!” Henry launched his peroration with a direct response, invoking the authority of Jeremiah: “Gentlemen may cry, ‘Peace! Peace!’—but there is no peace.” Henry embraced the full theatricality of his oratorical genius. First, exaggerating his characteristic stoop, he crossed his hands as if enchained. But then he suddenly propelled himself upward to his full height, hurling his arms apart as if throwing fetters to the winds. Henry was speaking with his body as well as his tongue. In triumphant tones, he declared: “I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty—” He paused to let the word echo. Then, raising his right hand as if he held a dagger, he cried, “Or give me death!” And he thrust his hand to his heart.

Some observers remembered a paper cutter in his hand, and one of whalebone with a very complex provenance is displayed as the object in question at the Patrick Henry National Memorial, a museum at his last home and grave site, in Charlotte County, Virginia. Whether or not he used a prop, Henry was able to transform a theoretical British threat into a real and tangible assault on his own body. Like a convert testifying at a revival gathering, Henry was making a bold personal and public commitment to his faith in the “holy cause of liberty.”

The delegates sat silent. Henry had defeated any rational basis for opposition to resistance by claiming that the war had already begun, and that there was thus no argument to be had at all. But their silence did not represent just a quiet acquiescence to the force of his reason. His words were too serious and of too much import to be greeted with cheers and huzzahs. The delegates were emotionally spent by what he had required of them—with his relentless interrogation of their courage and integrity, with his repeated reminders of the crucial line between freedom and slavery, and with the shock of the performance of a life-and-death moment before a staid deliberative body. Henry had made revolution seem not just inevitable but necessary; he had converted the delegates to his cause, with all the risks and costs it would entail. They now had the privilege and burden of a new and daunting responsibility. In their silence, they recognized that sobering reality—and the dangerous path before them.

A little more than a year after Henry inspired and propelled Americans into military conflict, the “thirteen united States” proclaimed themselves a nation. The Declaration of Independence was put to a vote of the Continental Congress not as the handwritten parchment manuscript we can all see in our mind’s eye. It was written to be read aloud; Thomas Jefferson marked the document to indicate his desired phrasing and pauses. The Declaration was first delivered as a speech.

Speech caused and then defined the Revolution. Speech became the engineer of consent. A trope emerged in the early years after the Revolution: describing the United States as a nation “spoken into existence.”

More than a century ago, the eminent historian Carl Becker defined the stakes of the American Revolution. The two paramount issues, he wrote, were the question of home rule (separation from Britain) and the question of who should rule at home (the character of a new American government). Patrick Henry’s oratory represented the intersection—and apotheosis—of these two imperatives. There was no more eloquent advocate for independence. But Henry’s ability to galvanize support for the American cause rested on his success in rousing those who had not before been welcomed as full participants in political discourse and action. His oratory embodied the transfer of authority not just away from the King, but into the hands of the newly created citizens who were soon to be promised that all were created equal. Americans would not of course be even politically equal for many generations to come. Property ownership as a requirement for voting was only gradually abolished in the years leading up to the Civil War; women did not gain the right to vote for more than a century; African Americans were not truly enfranchised until the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Yet Henry’s oratory set the emerging nation on a path toward these unfolding freedoms. His words—his appeal to heart as well as mind, to music as well as reason, to the transcendent as well as the temporal—made revolution seem imperative. The new nation would have no king, no standing armies to enforce the government’s will. In 1806, John Quincy Adams observed that power and authority in the new American nation rested on the “arms” of “persuasion.” Patrick Henry was the Revolution’s consummate persuader.

This article appears in the November 2025 print edition with the headline “No One Gave a Speech Like Patrick Henry.”